The wellness conversation around cannabinoids is shifting beyond THC and CBD to include rare compounds that may fine-tune mood. Cannabicyclol (CBL) is one of those emerging players: a non-intoxicating cannabinoid that forms naturally as cannabichromene (CBC) ages under light or acidic conditions. Although it occurs in tiny amounts and remains understudied, early science and what we know about stress biology point to plausible roles for CBL in stress relief and emotional regulation—paired with clear caveats about the current evidence base.

First, a quick primer on how stress is regulated. The body’s endocannabinoid system (ECS)—notably CB1 and CB2 receptors along with the neurotransmitters anandamide and 2-AG—helps maintain emotional homeostasis and reins in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the core stress-response network. When the ECS is functioning well, it dampens excessive stress signaling, modulates serotonin and GABA circuits, and supports resilience after acute stressors. Multiple reviews underscore this ECS–HPA connection and its relevance to mood and anxiety.

Where might CBL fit? A notable 2025 natural-products study found that racemic CBL acts as a potent positive allosteric modulator (PAM) of serotonin-induced activation at low concentrations—essentially amplifying the brain’s response when serotonin binds its receptor—while behaving only as a weak agonist at high concentrations. Serotonin signaling is central to emotion regulation, sleep, and stress adaptation; PAMs are particularly interesting because they can enhance native signaling without forcing the system in one direction. This pharmacology suggests a theoretical pathway by which CBL could help “nudge” mood circuits rather than override them. Human data do not yet confirm clinical benefits, but the receptor-level signal is compelling.

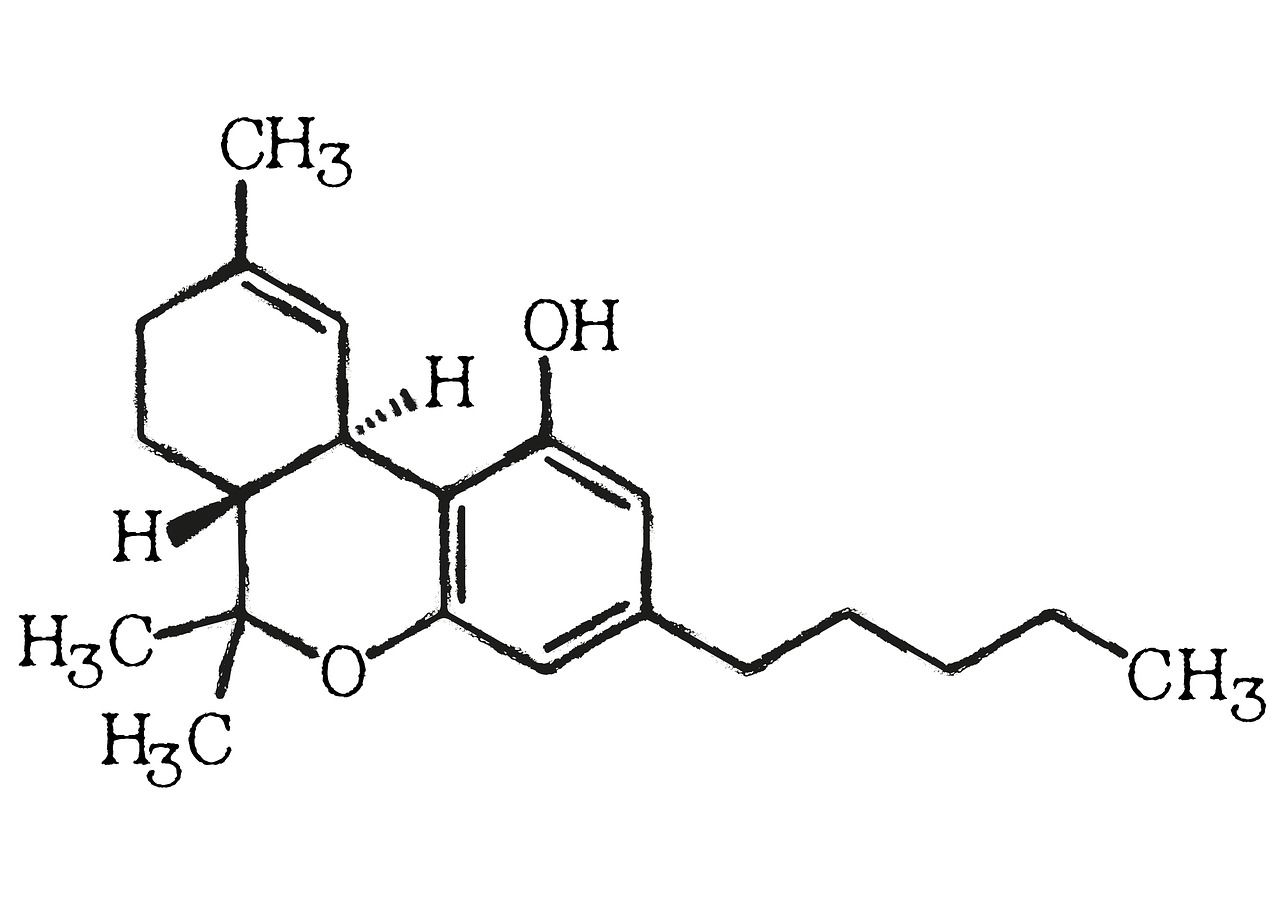

CBL also appears to be non-psychoactive, which matters for wellness users who want emotional balance while staying clear-headed. That non-intoxicating profile has been described in overviews of the molecule and aligns with its structural lineage as a degradant of CBC rather than THC. Still, “non-intoxicating” is not the same as inert—any bioactive compound can have effects, interactions, or side effects, especially at higher doses.

What does this mean in practice today? Because CBL naturally occurs in trace amounts, most consumer products—if they contain it at all—carry only micro-to-low milligram levels, and standardized CBL extracts are not yet common. If you’re exploring a wellness routine that includes CBL (often alongside CBD, CBC, or CBG), consider these evidence-informed guardrails:

- Expect subtlety, not sedation. If CBL’s serotonin-PAM activity translates in humans, the effect may feel like smoother edges rather than a dramatic shift. Track mood, sleep, and stress reactivity over weeks, not hours.

- Mind drug interactions. Like other cannabinoids, CBL could influence cytochrome P450 enzymes, which metabolize many medications. Discuss new cannabinoid products with a clinician, especially if you take SSRIs, benzodiazepines, or sleep aids.

- Prioritize transparency. Look for third-party lab reports that quantify minor cannabinoids; if CBL is listed, check actual milligrams per serving rather than relying on marketing copy. (Scarcity means robust labeling is essential.)

- Layer with lifestyle. Breathwork, consistent sleep, daylight exposure, movement, and nutrition all bolster the ECS and serotonin networks CBL may touch—stacking small wins produces outsized stress relief.

Finally, be realistic: anxiety and mood benefits observed with other non-intoxicating cannabinoids (most notably CBD) cannot be assumed for CBL until human studies arrive. For now, CBL is best viewed as a promising, mechanism-aligned adjunct rather than a standalone solution. If you choose to experiment, go low and slow, document how you feel, and integrate it within a broader, evidence-based stress-care plan.