Minor cannabinoids—think CBC, CBL, CBN, and friends—occur in trace amounts in the plant. That scarcity tempts labs to synthesize or convert them to reach meaningful volumes for research and products. But between tricky chemistry, scale-up headaches, analytics, and regulation, the road from benchtop to bottle is bumpy.

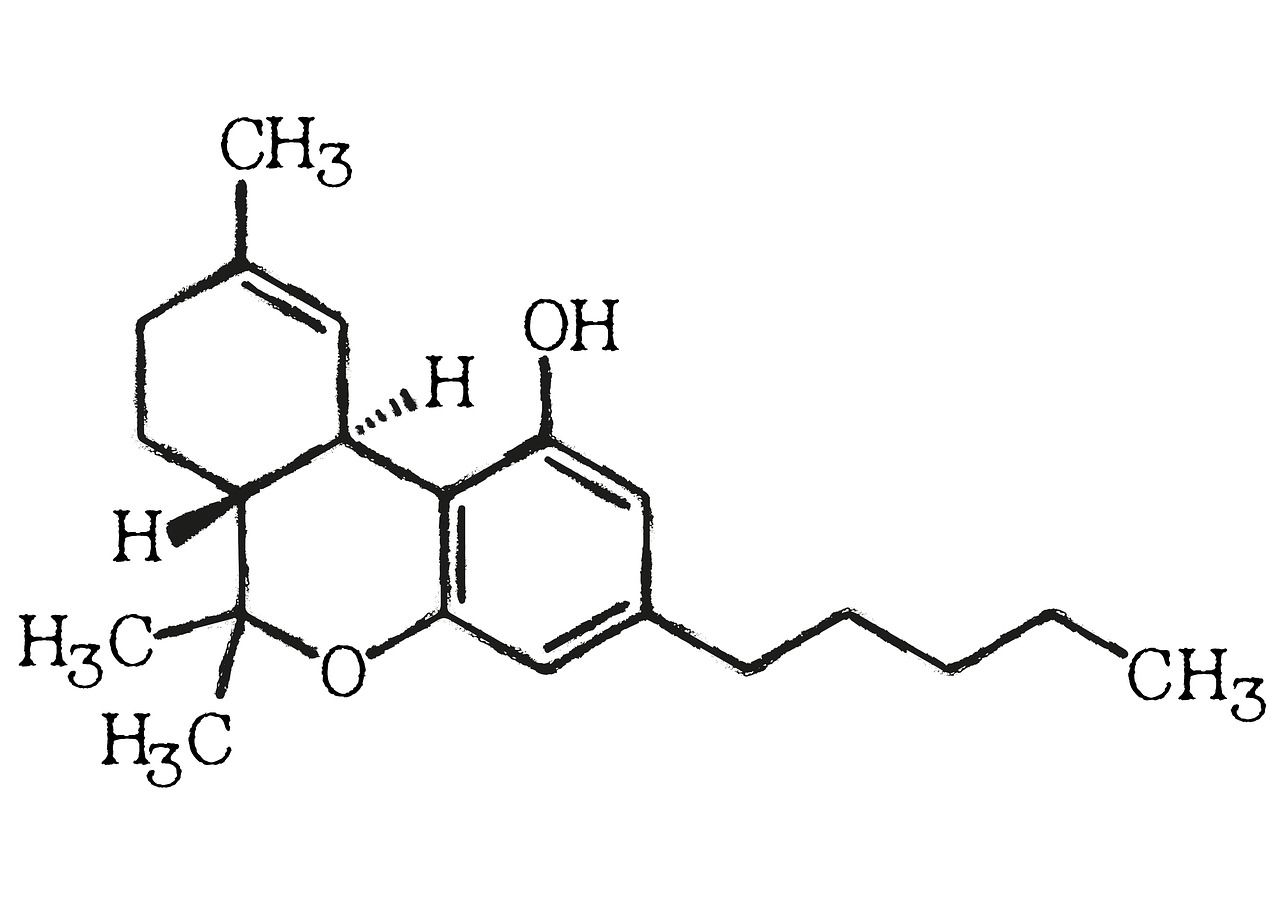

Start with the chemistry. In the plant, CBC is produced enzymatically from CBGA via a CBC-synthase step; nature does the selectivity work for free. Try to recreate or redirect that pathway in glassware, and you quickly confront trade-offs among yield, purity, and side reactions. A good example is CBL: it’s not biosynthesized directly in cannabis but typically forms when CBC rearranges under light/heat. Chemists can accelerate that conversion with catalysts, yet conditions that boost yield can also create isomers and unknowns you now have to separate and characterize. Recent lab work converting CBC to CBL reports improved yields under carefully chosen acidic catalysts, underscoring how sensitive outcomes are to solvent, temperature, and time—and why reproducibility is a constant battle.

Photochemistry adds another layer of complexity. Light-driven rearrangements (the same kind that slowly turn CBC to CBL in aged flower) can be efficient but unforgiving at scale: photon flux, path length, and heat management all impact product distribution. Even small drifts create impurity profiles that change from batch to batch, complicating method validation and shelf-life claims. Studies mapping cannabinoid photobehavior reinforce that exposure conditions can radically alter products, demanding tight process control and robust analytical fingerprints.

What about skipping chemistry and going bio? Engineered microbes and fungi are making headway, producing rare cannabinoid scaffolds from sugars. The promise is tunable selectivity and cleaner impurity profiles than harsh conversions. The reality: titers remain modest for many targets, pathway balancing is delicate, and downstream purification still costs real money. Nonetheless, recent work shows yeast strains cranking out non-common cannabinoid acids, and reviews highlight rapid synthetic-biology progress—encouraging signs, but not yet a magic wand for every minor cannabinoid.

Analytics and standards are the next hurdle. If you make a molecule that scarcely exists in nature, you also need reference standards, validated methods, and impurity specs that regulators (and customers) can trust. Labs must separate closely related isomers, quantify residual catalysts or solvents, and demonstrate stability across packaging formats and time. That’s resource-intensive, especially when demand is still forming and unit economics are tight.

Then there’s the regulatory fog. Conversions used to create rare cannabinoids have been scrutinized after safety issues with intoxicating hemp derivatives, prompting FDA and FTC actions and state-by-state rulemaking. Even if a target compound (like CBC or CBL) is non-intoxicating, the process used to make it, the byproducts it leaves, and the claims on the label can trigger enforcement. Companies have received warning letters for marketing cannabinoid products that skirt federal food and drug rules, and policymakers continue to debate how to treat synthetically derived or converted cannabinoids in the next Farm Bill cycle. For producers, that means building GMP-grade documentation, conservative claims, and supply-chain transparency into the plan from day one.

Where does that leave the industry? Short term, expect niche runs of high-purity minors (CBC today, potentially CBL tomorrow) coming from either best-in-class conversions with rigorous cleanup or from fermentation platforms that hit acceptable titers. Long term, winners will pair selective production with gold-standard analytics, clear safety dossiers, and regulatory fluency. The science is advancing, but scaling minor cannabinoids from curiosity to category will reward the patient, the precise, and the transparent.