When cannabis material is exposed to strong light or sunlight, one lesser-known cannabinoid may gradually build up: cannabicyclol (CBL). The key underlying chemistry: sunlight drives the conversion of cannabichromene (CBC) into CBL. Understanding this process helps cultivators, manufacturers, and consumers alike appreciate how storage, harvesting, and post-processing affect cannabinoid profiles.

From CBC to CBL: How it happens

CBC originates in the plant via the standard cannabinoid biosynthetic pathway. The precursor molecule cannabigerolic acid (CBGA) is converted by an enzyme into cannabichromenic acid (CBCA) and then, via decarboxylation, into CBC.

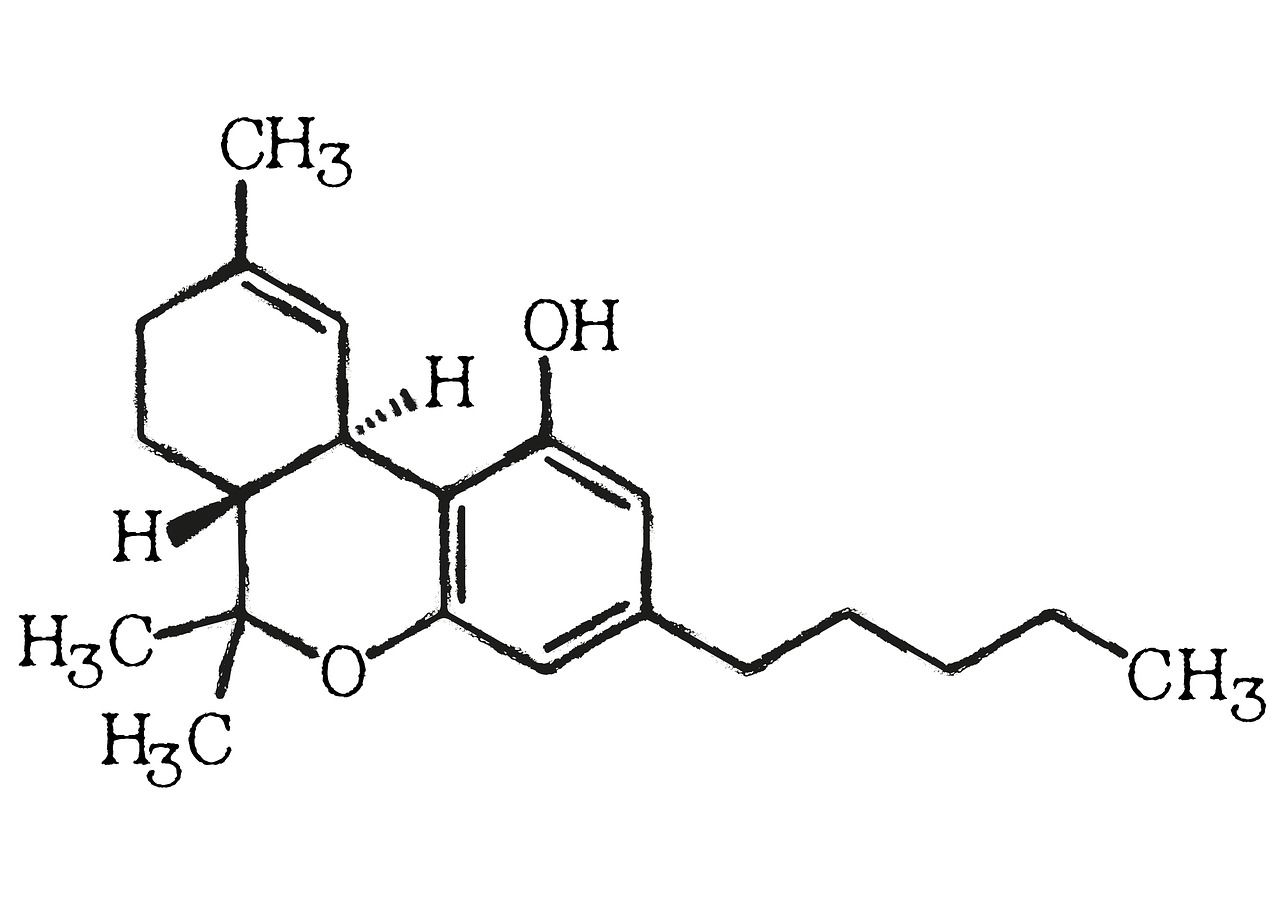

Once CBC exists (in plant material or extract), exposure to ultraviolet (UV) or intense visible light can trigger a photochemical reaction. In that reaction, CBC rearranges its molecular structure—essentially forming a bicyclic ring system—to become CBL. The photochemical nature of the reaction has been recognized as far back as the 1960s.

Why sunlight matters

Light functions as a reagent here: photons carry sufficient energy to break or rearrange chemical bonds in CBC under the right conditions. When flower or extracts sit in higher-light environments (for example, clear packaging under sunlight or outdoor drying in strong sun), the rate of conversion to CBL increases. Additionally, factors like heat and oxygen amplify degradation pathways overall, though the specific CBC→CBL route is driven by photon-induced rearrangement.

When you test older, sun-exposed material (or mis-stored biomass), you often see higher CBL and lower “fresh CBC” levels. That doesn’t necessarily imply anything nefarious—just that the chemistry has progressed. In essence, sunlight = reagent; time = reaction.

Implications for cultivation, processing and storage

- For preserving CBC: If the goal is to maintain higher levels of CBC in biomass or extraction output, the material should be protected from UV light as early as harvest. Use opaque or UV-blocking bags, store in dark cool places, and avoid high-intensity drying under direct sun. These practices slow down the conversion to CBL.

- For analytic interpretation: Lab results that show elevated CBL may reflect storage or light exposure history rather than genetic differences. When analyzing cannabinoid profiles, handling history becomes part of the story.

- For product formulation: While CBC is an active cannabinoid under study, CBL remains far less characterized. The conversion doesn’t create a new “intoxicating” compound—in fact, CBL is considered non-psychoactive—but it does change the spectrum of minor cannabinoids present.

- For aging or archival material: Older flower or extracts, especially those stored in translucent or semi-exposed containers, tend to accumulate CBL over months or years. This again is simply chemistry in motion rather than contamination.

Key take-aways

- The major takeaway: sun/UV light converts CBC → CBL via a photochemical route.

- Protecting cannabinoids from light can preserve desired profiles; conversely, if you don’t care, light will just change the profile for you.

- CBL formation is not inherently bad—it’s simply a marker of exposure/age/light-history—but if your goal is CBC, you must treat light like an unwanted reagent.

- More research is needed on CBL’s biological effects and role within the “entourage” of cannabinoids, so the presence or absence of CBL may matter in formulation, quality or function.

In short: when cannabis says “sunlight please” for growth, afterwards that same sunlight can quietly convert one cannabinoid (CBC) into another (CBL). The chemistry is subtle but significant, and understanding it helps refine cultivation, extraction, storage and interpretation of cannabinoid analytics.