In the intricate world of cannabinoids, cannabicyclol (CBL) stands out not for its potency but for its remarkable chemical transformation. Unlike cannabinoids such as THC or CBD, CBL isn’t synthesized directly by the cannabis plant. Instead, it is a product of time, light, and chemical rearrangement—a byproduct of nature’s slow alchemy that turns one compound into another. To understand CBL’s unique properties, it’s essential to look at its molecular structure and the reasons behind its exceptional stability.

A Structural Shift from CBC to CBL

CBL begins its chemical life as cannabichromene (CBC), one of the lesser-known cannabinoids produced naturally by the plant. When CBC is exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light or heat, a photochemical reaction occurs. This reaction causes the molecule’s double bonds to rearrange and form a new ring system, creating CBL. The process is known as photoisomerization—a reaction in which light energy breaks and reforms chemical bonds within a molecule.

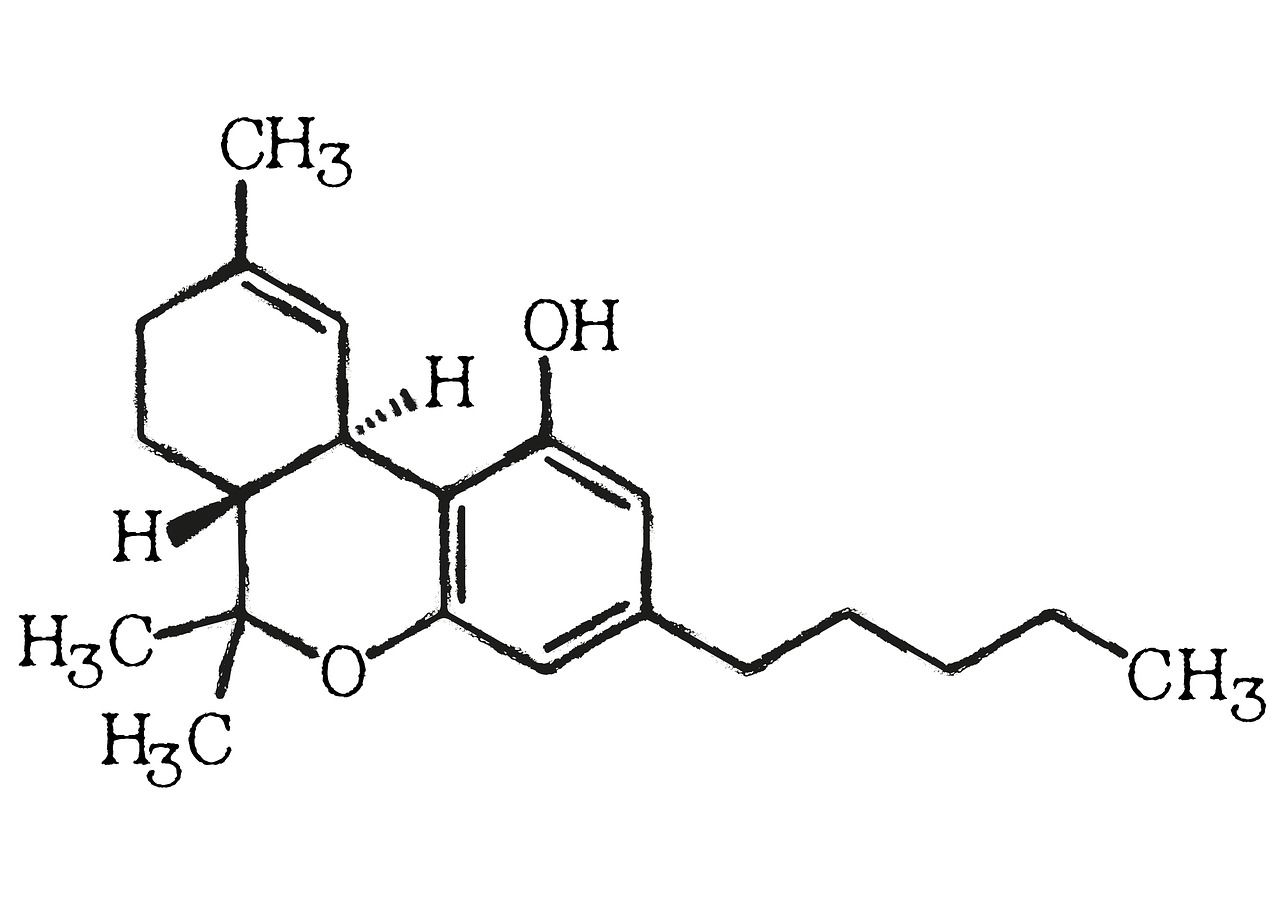

Structurally, CBL differs from CBC by the saturation of the double bond in the cyclohexene ring. This small molecular adjustment results in a bicyclic compound that lacks the reactive sites found in CBC and THC. In essence, CBL’s stability is built into its structure. Its rigid, closed-ring framework resists oxidation and degradation, giving it a chemical resilience rarely found among cannabinoids.

The Molecular Blueprint: Why CBL Holds Its Form

Chemically, CBL’s molecular formula is C₂₁H₃₀O₂, identical to many other cannabinoids. However, its three-dimensional configuration defines its distinct behavior. CBL contains a fused bicyclic core, which prevents the molecule from readily participating in further reactions. The absence of a double bond in the key position—unlike in THC’s delta bond—makes CBL far less prone to oxidation or rearrangement.

This rigidity makes CBL thermally and photochemically stable, even under conditions that would cause other cannabinoids to degrade or convert. Studies have shown that while compounds like THC and CBD lose potency over time through oxidation and decarboxylation, CBL remains largely intact. This chemical stability suggests potential applications in formulations where long shelf life and structural integrity are critical—such as pharmaceutical-grade extracts or scientific reference materials.

CBL’s Non-Psychoactive Nature and Chemical Inertness

Another result of CBL’s structure is its lack of psychoactivity. The absence of a free phenolic hydroxyl group and a reactive double bond means CBL cannot effectively bind to the CB1 receptor, the molecular site responsible for THC’s intoxicating effects. This chemical inertness places CBL among other non-psychoactive cannabinoids such as CBD, CBG, and CBC. Yet its unique stability and minimal reactivity may make it a valuable candidate for studying long-term cannabinoid interactions in biological systems.

Because CBL resists degradation, it can act as a stable chemical marker in aged cannabis. Researchers often use its presence to assess storage conditions, light exposure, and the aging process of stored plant material or concentrates. In a sense, CBL functions as a molecular “timestamp,” signaling how long and under what conditions cannabis has been kept.

CBL’s Chemical Promise

While CBL currently exists in trace amounts in most cannabis strains, scientific interest is growing. Advances in synthetic chemistry could allow researchers to reproduce CBL in larger quantities, enabling studies into its potential anti-inflammatory or neuroprotective roles. Its inherent molecular stability could make it a reliable component for drug formulations, offering a chemically inert framework for structural analogs or novel cannabinoid-based medicines.

Ultimately, Cannabicyclol represents a fascinating case of molecular evolution within the cannabis plant — a stable product born from light, time, and chemistry. Its unyielding structure doesn’t just resist change; it tells the story of it.